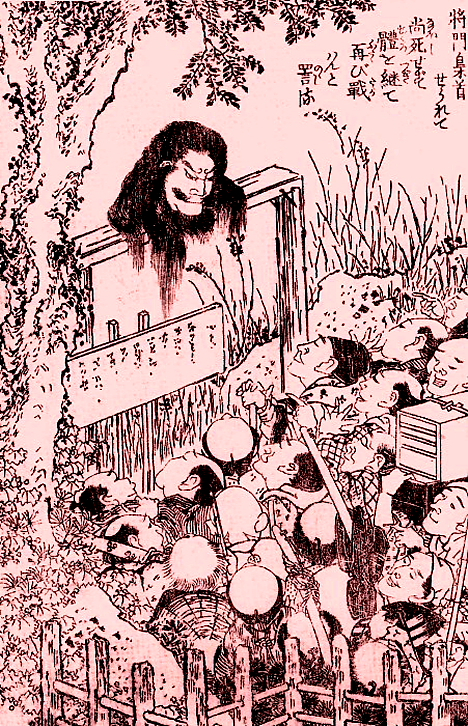

Tales of "human pillars" (hitobashira) -- people who were deliberately buried alive inside large-scale construction projects -- have circulated in Japan since ancient times. Most often associated with castles, levees and bridges, these old legends are based on ancient beliefs that a more stable and durable structure could be achieved by sealing people inside the walls or foundation as an offering to the gods.

Was a young woman buried alive inside the wall of Matsue castle long ago?

One of the most famous tales of construction-related human sacrifice is associated with Matsue castle (Shimane prefecture), which was originally built in the 17th century. According to local legend, the stone wall of the central tower collapsed on multiple occasions during construction. Convinced that a human pillar would stabilize the structure, the builders decided to look for a suitable person at the local Bon festival. From the crowd, they selected a beautiful young maiden who demonstrated superb Bon dancing skills. After whisking her away from the festival and sealing her in the wall, the builders were able to complete the castle without incident.

However, the maiden's restless spirit came to haunt the castle after it was completed. According to folklorist Lafcadio Hearn, who described the castle's curse in his 1894 work "Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan," the entire structure would shake anytime a girl danced in the streets of Matsue, so a law had to be passed to prohibit public dancing.

Although there is no conclusive evidence indicating that construction-related human sacrifice was actually practiced in Japan, it has been suggested that some laborers may, on occasion, have been terminated as a security measure after working on castles. Doing so would have prevented knowledge of a castle's secrets and weaknesses from falling into enemy hands.

Other notable structures rumored to make use of human pillars include:

- Gujo-Hachiman castle (Gifu prefecture)

- Nagahama castle (Shiga prefecture)

- Maruoka castle (Fukui prefecture)

- Ozu castle (Ehime prefecture)

- Komine castle (Fukushima prefecture)

- Itsukushima shrine (Hiroshima prefecture)

- Fukushima bridge (Tokushima prefecture)

- Kintaikyou bridge (Yamaguchi prefecture)

- Hattori-Oike reservoir (Hiroshima prefecture)

- Imogawa irrigation channel (Nagano prefecture)

- Karigane embankment (Shizuoka prefecture)

- Manda levee (Osaka prefecture)

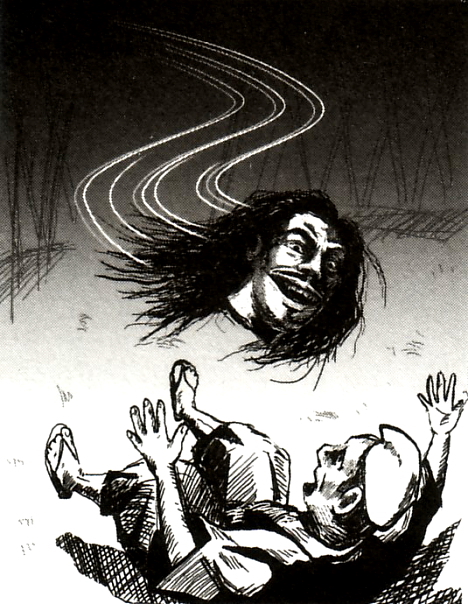

Modern-day versions of these old legends can also be found on Japan's northern island of Hokkaido. Human bones have been found around several bridges and tunnels, lending an air of credibility to rumors that workers were sacrificed during construction.

Monument erected after skeletons were found sealed in the walls of Jomon tunnel

Jomon tunnel, constructed on the Sekihoku Main Line (JR Hokkaido) in 1914, is notorious for rumors of human sacrifice. In 1968, the tunnel underwent repairs after a major earthquake damaged part of the wall inside. While doing the renovations, workers found a number of human skeletons, standing upright, sealed inside the walls. A large quantity of human bones were also unearthed near the tunnel. The discovery fueled beliefs that the tunnel was constructed with human pillars, and many people -- including train conductors -- came to fear that the tunnel was haunted by the ghosts of the victims.

Some theories suggest that brutal working conditions and poor nutrition led many workers -- mainly criminals and debtors working against their will -- to contract beri beri, a deadly nervous system ailment. With no access to medicine, these victims are believed to have been buried alive near the construction site. A monument honoring the fallen workers was erected in 1980.

Were people sealed inside the concrete supports of Koshikawa bridge?

People are also rumored to have been sealed inside the concrete supports of Koshikawa bridge, on the now-defunct Konboku line (also in Hokkaido). While no actual human skeletons have been found, recent surveys have revealed the possible existence of hollow spaces in the structure that may contain human remains. Records indicate that at least 11 indentured workers may have died building the bridge, which was completed in 1939.

[Note: This is the latest in a series of weekly posts on Japanese urban legends.]

Italy Pavilion [

Italy Pavilion [

Barbie goes to Expo '70 [

Barbie goes to Expo '70 [