A severed samurai head buried in central Tokyo has struck fear and awe in the hearts of locals for over 1,000 years.

The head that refused to die

The head -- supposedly buried in the Otemachi district -- belongs to Taira no Masakado, a rebellious warrior who led an insurgency against the central government in the 10th century. At the height of his power, Masakado proclaimed himself emperor -- an act that aroused the wrath of the government and ended in his decapitation. The samurai failed to become ruler of Japan, but his severed head has remained a persistent source of trouble for over 1,000 years.

Here is a brief history of the head.

903 - 940 AD: Taira no Masakado was born and raised in eastern Japan. After leading a minor rebellion and assuming control of eight provinces in northern Kanto, Masakado declared himself the new emperor of Japan. The established emperor, based in Kyoto, responded by putting a bounty on his head. Two months later, Masakado was killed in battle. His decapitated head was transported to Kyoto and put on public display as a warning to other would-be rebels.

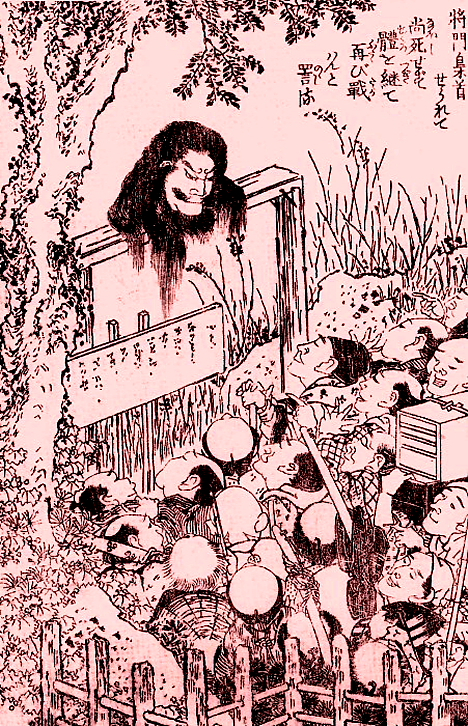

Masakado's head on display in Kyoto

Strangely, Masakado's head did not decompose. Three months later, it still looked fresh and alive, though the eyes had grown more fierce and the mouth had twisted into a horrifying grimace. One night, the head began to glow, and it lifted into the air and flew off in the direction of Taira no Masakado's hometown.

The head grew weary on the long flight home, and it came to rest in the village of Shibasaki (present-day Otemachi, Tokyo). The villagers picked up the head, cleaned it, and buried it in a mound at Kanda Myojin shrine.

950: Ten years after the head was laid to rest, the burial mound began to glow and shake violently, and the ghost of a bedraggled samurai started to make regular appearances in the neighborhood. The frightened locals offered special prayers that seemed to put the spirit to rest.

1200~: At the beginning of the 13th century, a temple belonging to the powerful Tendai Buddhist sect was built adjacent to Kanda Myojin shrine. This apparently upset the spirit of Masakado, and the people in the area were stricken by plague and natural calamities as a consequence.

1307: Nearly a century later, a priest from an Amida Buddhist sect -- which took a more liberal, accessible approach to Buddhism than the Tendai sect -- built an invocation hall here and tended the shrine of Masakado, thus easing the spirit's anger.

Over time, Taira no Masakado came to be regarded as a deity in east Japan

1616: Kanda Myojin shrine, which had elevated Masakado to deity status, was moved to a new site to make room for the mansions of the feudal lords stationed in Edo. The burial mound and headstone were left behind in the garden of one of the mansions.

1869: After the fall of the feudal system, the Meiji government constructed their Finance Ministry building next to the burial site. The mound and headstone were left untouched.

1874: The government issued a formal declaration condemning Masakado as having been an "enemy of the emperor." His deity status at Kanda Myojin shrine was revoked.

1923: The Great Kanto Earthquake and the ensuing fires all but destroyed the mound and stone monument. The Finance Ministry building burned to the ground. Before rebuilding, the ministry excavated the grave site in search of the skull, but found nothing. They decided to erect a temporary building on the premises.

1926: Building over the burial site turned out to be a terrible decision. Finance minister Seiji Hayami died suddenly of illness, and 13 other ministry officials met similar fates over the next two years. Many workers became ill or were injured in mysterious accidents on the premises. People believed that Taira no Masakado had cursed the new building.

1928: The ministry removed part of the structure covering the burial site and began holding annual purification rituals. At first there was great enthusiasm for the rituals, but interest faded over the years.

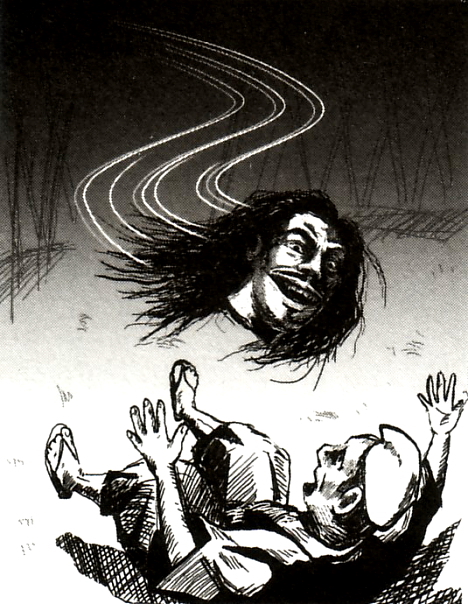

Masakado's head takes to the skies

1940: A fire sparked by lightning burned down the Finance Ministry building and several other government offices in the Otemachi district. The day was remembered as being exactly 1,000 years after the death of Taira no Masakado. The old earthquake-damaged stone monument was rebuilt, and the site was rededicated to the samurai rebel. The Finance Ministry moved, and the land around the burial site became the property of the Tokyo municipal government.

1945: After World War II, US occupation forces seized control of the property and began to clear the land to create a parking lot. Progress was hindered by a series of suspicious accidents. In one accident, a worker died next to the grave when the bulldozer he was driving flipped over. After local officials explained the significance of the burial site to the US forces, they decided to leave part of the parking lot unfinished.

1961: Control of the property was handed back to Japan, and the parking lot was removed. Purification rituals were conducted, and the burial site was once more dedicated to Taira no Masakado. But when new buildings were constructed next to the burial mound, workers again fell ill. A figure with disheveled hair reportedly began to appear in photographs taken in the area. In an attempt to calm the spirit, representatives from local businesses started to pray at the burial site on the 1st and 15th of each month.

The final resting place of Masakado's head - Google Street View // Google Maps

1984: In response to public pressure following the broadcast of an NHK television drama based on the life of Taira no Masakado, his deity status at Kanda Myojin shrine was reinstated.

1987: A string of freak accidents and injuries occurred during the filming of Teito Monogatari ("Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis"), a historical fantasy whose villain seeks to destroy Tokyo by awakening Masakado's spirit (watch the movie trailer). To prevent accidents on the set, it is now common practice for TV and movie producers to pay their respects at the burial site before bringing Taira no Masakado to the screen.

In the more than 1,000 years since Masakado's head fell from the sky, Tokyo has grown into the world's largest metropolis and the area around the burial site has become the financial center of Japan. But to this day, local business people remain wary of the power of the head in their midst, and the surrounding companies take great pains to keep Masakado's vengeful spirit in check. Supposedly, no office worker in the vicinity wants to sit with their back toward the burial site, and nobody wants to face it directly.

[Note: This is the latest in a series of weekly posts on Japanese urban legends. Check back next week for more.]

R Cox

Masakado's head is a great story and great mystery. In America we have a similiar mystery concerning the head of the indian war chief, Geronimo. It is said that Sen. Prescot Bush, George W. Bush's grandfather stole the head from its grave and placed it in a trophy case in the War hall of the Skull and Bones society.

Even if no power exists from the object itself, power manifests through the minds of others as they contemplate the mystery.

[]m

Ever since I visited the Masakado Kubizuka a few years ago, I've always wondered why people leave the kitschy little frog statues there. Does anyone know why?

[]ben t

"...why people leave the kitschy little frog statues there. Does anyone know why?"

Not sure if this is related to that custom, but a quick google search for led me to http://books.google.co.jp/books?id=D7NC4dVU_jcC&lpg=PA107&ots=6J4OezT9k5&dq=Masakado%20frog%20statues&pg=PA107#v=onepage&q=&f=false :

"On the eleventh, the Council of State issued a special directive...:

...He stands alone, [like the frog who] knows the breadth of the well bottom, but forgetting to safeguard against what lies beyond the sea..."

[pages 106-107]

I only skimmed this section, but I'm assuming that 'standing alone' refers to his act against the established emperor in Kyoto, and the 'frog in the well' refers to the Japanese proverb 「井ã®ä¸ã®è›™å¤§æµ·ã‚’知らãšã€â‰ˆ "The frog in the well doesn't know the ocean". (I rather like this kotowaza. To a certain extent we are all frogs in our own wells, are we not?)

However, now that I think about it, maybe this explanation doesn't relate to the statues. If his spirit strikes such fear, why would people make a gesture that comes across like saying, "Silly Masakado, you sure failed to see the big picture, didn't you?"

[]Froggy

Ben T,

Go here:

http://ishinotouei.com/okimono.html

If you scroll down, it briefly explains the play on words of "KAERU" (frog) which is also to mean "to return" or "to go back."

[]In the case of Masakado, I think it means that the people who have laid him to rest wish that good things return to him, instead of the opposite.

Billionz

Loving these posts.

[]Luca

pure gold, many thanks!

[]justin

this story is extremely interesting. i will definately try to read moe about it.

[]um...

i like the picture of the flying head and the dude freaked out laying on his back MWAHAHAHAHAHAHA

[]Kaitlin

as said in a previous post, in Japanese word for frog (Kaeru) also has the subtext/symbolism of good luck and i hope you return soon. I was in Japan on a school exchange 5 years ago and was given little frog statuettes quite frequently.

[]I'm assuming that the frogs around the shrine symbolize the return or the presence of Masakado. Again it could also mean to ward off bad spirits and bring good luck. I can't honestly say.

Shanahan

I love how the note attached to the head in the first picture says (in Romanji (the phoenetic spelling of japanese letters makin it easy for the average american)

[]HA

HA

HA

Katie AkaTako

Excellent post! Thank you for sharing the Japanese terror - not to mention the great illustrations that go along with it.

[]Buryoku

I really loooove that story!!!

I also wanted to ask your permission to use the pic. of the flying head for my blog if this is ok!

Thx and Greetz b.

[]superstitions

Yet places made fully out of skulls remain still untouched like Kutná Hora church for example.

[]